|

Water chestnut shells. Picture, South Karelian Museum / Seppo Pelkonen.

|

|

Red ochre grave at the Vaateranta burial ground in Taipalsaari. A small, intact clay cup was found at the foot end of the grave. Picture, National Board of Antiquities / Kaarlo Katiskoski.

|

|

Grave no. 3 in Vaateranta yielded amber pendants, among other items. They had been placed on the eyes of the deceased as for a death mask. Only the dental enamel remained of the dead. Picture, National Board of Antiquities / Kaarlo Katiskoski.

|

|

|

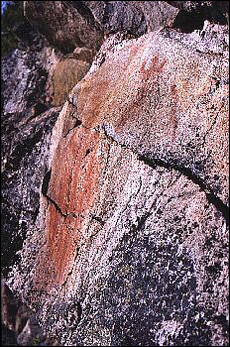

Rock painting at Kolmiköytisienvuori in Ruokolahti. Picture, South Karelian Museum.

|

Nature provided a favourable setting

During the Neolithic Period, the climate in South Karelia was as warm as it is in Central Europe today. Deciduous and pine forests grew on the shores of Lake Saimaa. People lived by fishing, hunting, and gathering. Bone findings indicate that the people who lived long ago on the Tervastenranta shore of Joutseno ate beaver, pike, and perch, for example. Other important game animals were seal, elk, and wild reindeer. Plants and berries were also gathered, but few traces of their use have survived. One interesting food plant used by Stone-Age man was the water chestnut, which now grow in the lakes as far north as Lithuania. Water chestnuts have also been found in old sediment deposits, such as those in Lake Jäkälä at Savitaipale.

Life on sandy beaches and at holy sites

The Stone-Age people travelled among familiar dwelling sites year after year according to where food was best available at a particular time of the year. The extended family probably formed the hunting group. At good sites people also settled all year long. Dwellings were erected on the sunny beaches. Trees were chopped from the forest on the shore and set in the ground to build a rectangular, house-like dwelling. The roof was probably rendered waterproof using birch bark, pelts or sod. Because the dwellings were often dug slightly into the ground, the bases of the dwellings of ancient peoples can still be seen as shallow oval indentations, for example, at the dwelling sites at Mietinsaari in Joutseno and at Hietaranta beach in Lappeenranta's Rutola. In addition to the more sturdy house, people also used more lightly constructed shelters or huts.

Other kinds of relics may also be connected to a dwelling site. Beneath the broad Combed Ware settlement at Vaateranta in Taipalsaari we have discovered a large burial ground containing red ochre graves, in which articles the deceased might possibly need on the other side have also been buried, such as spearheads, scrapers, slate and amber jewellery and, occasionally, also pottery. In addition to dwelling sites and burial grounds, Stone-Age people also left evidence of their beliefs. Figures of humans, elk, and what appear to be boats painted in red ochre on the smooth, vertical rock faces reflect the shamanistic philosophy of the northern hunting culture. At present 29 paintings or traces of colour are known in the South Karelia region, but every year more are found. The Kolmiköytisienvuori rock painting at Ruokolahti is the region's finest.

The people travelled from dwelling site to dwelling site by rowboat in summer and by sled and ski in winter. The waterways, ridges, heaths and frozen swamps provided convenient travel routes. Moreover, the waters provided water game, which occupied a prominent place in the Stone-Age menu.